By: Priscilla Hayes

It’s May 15, and I am finally completing a post about a wonderful session that took place a month ago. On Tax Day, April 15, 2015, we welcomed Jeff Quattrone to the New Jersey Audubon Plainsboro Preserve facility to talk to community and school gardeners about seed saving. Part of the reason this blog post is delayed is because it is prime school garden season and I have been in my three school gardens non-stop rather than at the computer. The other reason is the breadth of the April 15 session and of the intense discussion there. We covered some beginning seed saving tips complete with a demonstration of tomato seed saving. We also learned about the careful research and steps Jeff took starting three “seed libraries” and some legal issues that have lately arisen, in which states seemed to have difficulty distinguishing between regulation needed for those selling seeds versus those exchanging seeds non-commercially. After some struggle over how to convey all of this to you, I decided that on the latter, I would refer you to some online sources, including a New York Times article. Please see the list of links at the end of this article and in the blog’s resources section. Still, this post is longer than usual, and will be divided into sections.

THE POWER OF STORY

Seed saving involves stories of each of the seeds saved. We can look at seeds themselves as stories, and Jeff’s getting to seed saving and seed libraries is a story in itself. Jeff has a background and training as an artist, and he views all his ventures through an artistic lens. When he saw that the print graphic arts work he had been doing was disappearing in favor of digital forms of representation, he began trying to “reinvent himself,” drawing always on his arts base. In art school, he had learned both to challenge the prevailing notions of society and also to value stories as integral art in their own right. All of this led him to start a blog that featured a daily story about a person who was doing something positive to change the world. In the course of writing that blog, Jeff found himself coming back again and again to posts related to sustainability and gardening, and found himself especially drawn to the Ark of Taste, which is a project of Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity. The Ark of Taste is described online as “a living catalog of delicious and distinctive foods facing extinction. By identifying and championing these foods we keep them in production and on our plates.” https://www.slowfoodusa.org/ark-of-taste-in-the-usa

Jeff became passionate about the idea of keeping heirloom plants from becoming extinct, and had also developed an interest in promoting “food security,” i.e. making sure that people had enough good food to eat. He started a second blog, Vanishing Feast, An Heirloom Solution, described as intended

to bridge the gap between society today and the history and tradition of heirloom gardening. The focus will be on food sources that are endangered, and specifically on fruits and vegetables, and bring awareness to the tradition of seeds and or plants as family heirlooms.

SEED SAVING AND SEED LIBRARIES

Vanishing Feast gave Jeff new opportunities for his artistic outlets, celebrating the stories and variety of colors and textures that heirlooms offered. But Jeff realized that that, too, was only a step in his reinvention journey. He wanted to do more than blog about heirlooms—he wanted to actively work on saving them. It became clear to him that the action most within his power and abilities was seed saving and the starting of seed libraries to foster the community that is built over the sharing of saved seeds. Seed saving was also the best way for individuals to ensure food security, and Jeff felt especially lucky to be in New Jersey, where a three season harvest is possible. More than that, there were stories about each of the heirlooms and about the varieties that had disappeared. There were stories about the privatization of seeds, and the loss of biodiversity in food crops, while biodiversity was generally only thought of as a necessary element for wild plants and animals.

Since he had “always grown plants, not seeds,” one of his first tasks was to teach himself about pollination and seeds. He needed to learn about how to keep the genes of heirloom varieties pure. He quickly determined that “selfers,” i.e. those plants that pollinated themselves, would be good starter plants for beginning seed savers. Success with these plants could give them confidence to go on to the more challenging seed saving with wind or insect pollinated plants. He saw that seed saving could allow gardeners to develop seeds best adapted to their own local environment.

As another step in his research, Jeff looked to the models of seed banks already in place elsewhere. He became inspired by seed companies or individuals who were breeding vegetables for local environments, like “Radiator Charlie,” who originated the “mortgage lifter” tomato, so called because it was so big that he was able to make enough money off its seeds to lift his mortgage. He then looked to more formal seed saving operations, like Richmond Grows, (http://www.richmondgrowsseeds.org/) a seed library in Richmond, California that had stepped up to take the lead in providing resources, tools and data collection both about and to seed libraries starting around the country. Richmond Grows encourages beginning members to save seeds only from the “super easy” drawers of seeds that it makes available, also known as the selfers. Jeff also looked at the more local model of Hudson Valley Seed Library (http://www.seedlibrary.org/), although the latter sells the seeds its members save, not simply facilitating a non-commercial exchange of seeds.

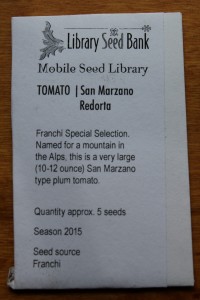

Jeff also thought long and hard about the envelopes to be used for seed sharing, and settled on coin saving envelopes as the perfect ones. The sample that he gave seminar goers, that is pictured here, is 2 ¼ by 3 ½ inches. As the photo shows, it contains the seed variety name, a short description of its backstory, the quantity enclosed, season, and seed source.

After a year of research, Jeff began approaching possible municipal venues and opened his first library in February 2014, followed by two more in 2014 and this year. The seed libraries “check out” seeds to patrons, with a promise from them that they will return seeds at the end of the growing season. While there are a variety of seeds available for checking out, the seeds which patrons are asked to return are those of open pollinated or heirloom plants, and are generally “selfers.” “Selfers” are plants which can pollinate themselves, and thus can be expected to breed true to the parent plant without the need for hand pollination and protection of flowers from pollen brought by insect or wind. Only experienced seed savers are invited to save more challenging varieties.

THE BEGINNING SEED SAVER

Jeff recommended that the beginning seed-saver start with “selfers,” tomatoes, peas, lettuce and beans, and then move on from successes with these to other plants. In the April 15 session, he demonstrated removing seed containing pulp from a tomato and placing it into a jar of water, where it should remain for three days to ferment. The seed would then be washed to remove seeds from the pulp over a small seed screen, which was basically a frame around screen material.

A seed saver who had gotten confidence with these first, easy plants could move on to more challenging items, such as squashes. Jeff provided all of the seminar participants with a list of recommended distances between any insect pollinated plants that could breed with each other. He also showed us silken bags to use to assure that no insects sneak in to bring unwanted pollen to a plant being raised for seeds. These bags ranged from drawstring bags available for wedding favors, which could cover a single flower, to larger silken bags to cover a whole plant or significant part thereof.

Of course the seminar could only whet our appetite for starting seed saving, especially since we were attending it at a time when there were no seeds to be saved, but only planning to be done. I can see that learning seed saving is a process, and am doubly glad that I have the continuing opportunity to learn slowly, through the season-long training at Duke Farms, the next session of which I will attend tomorrow.

LEGAL ISSUES LINKS

In the interests of making sure that farmers and others buying seeds are getting what they paid for, various states are regulating non-commercial seed savers as well. While he is not a lawyer and it is important to come to your opinion, Jeff believed that New Jersey law is clear enough to support the non-commercial distinction and won’t lead to this imposition of excess regulation on seed savers. Those interested in learning more about the topic can consult the following links.

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2014/12/28/us/ap-us-seed-struggle.html?_r=0

http://www.resilience.org/stories/2015-02-12/seed-libraries-fight-for-the-right-to-share